Presiona aquí para ver la versión en español

Two moments tend to bookend mainstream accounts of U.S. disability history. On one end, we learn about the rise of psychiatric hospitals in the early 19th century. At the other, we celebrate the 1990 passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act. [1] But disability history doesn’t just belong to the past. The history of people with disabilities is an ongoing project that intersects with identity, law, protest, and how we move about the world around us.

One article cannot cover the entire history of people who have lived and live with disabilities across the U.S. People have always lived with disabilities, and different cultures understand disability in different ways. But we can locate a persistent theme throughout American history: others have defined and made decisions about us. But we continue to fight for self-determination, or the right to make decisions about and for ourselves. The fight for self-determination and disability rights is also intertwined with other movements.

“Self-advocacy” refers to people’s willingness to stand up for themselves. Self-advocacy is central to the disability rights movement and the ongoing struggle for disability justice. This movement began among localized groups in the early 1900s. Later, these groups joined forces under a broader umbrella. This article introduces the stories of two women whose histories are part of larger trends in this movement.

The 1960s and ‘70s were an era of social change. Civil, women’s, and LGBTQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer) rights movements expanded across the U.S. This period was marked by progress, but also of at-times violent struggle. People with disabilities participated in and led these movements. Examples include groups of disabled veterans who smashed sidewalks and created curb cuts where none had been. Elsewhere, people with disabilities stormed the Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) building in San Francisco. Activists spent 25 days at HEW engaging in non-violent protest. Members of the local Black Panthers brought them meals. The protest was a success, and politicians agreed to pass laws to support accessibility.

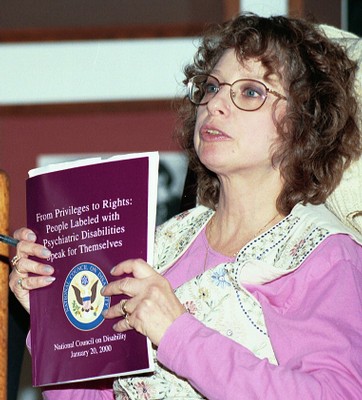

It was during this time that Judi Chamberlin and Ruth Sienkiewicz-Mercer were confined to psychiatric hospitals against their will. Their lives were affected by changes both within and outside of the hospital. They helped reshape how we understand “treatment” for people with disabilities today. Their books I Raise my Eyes to Say Yes by Sienkiewicz-Mercer (1989) [2] and On Our Own: Patient-Controlled Alternatives to the Mental Health System by Chamberlin (1979) offer insight into their roles in the disability rights movement.

Ruth was born nondisabled but became severely ill as an infant. As a result of this illness, she contracted cerebral palsy. Unable to move her limbs or speak, she communicated with facial expressions, chirps and coos, and teeth chatters. In 1962, while still a child, Ruth’s family sent her to Belchertown State School in Massachusetts. [3] She stayed there until 1978. This facility, however, did not adequately care for Ruth. Instead, they neglected, ignored, and abused her. According to Ruth, “my intake evaluation labeled me an imbecile, and thus determined how the nurses and attendants were to treat me for the next few years. Since everyone assumed that I couldn’t understand what was going on around me, they ignored any and all evidence that I could present to the contrary. I cannot view this label as an understandable mistake, because it took nearly ten years before it was officially changed” (Sienkiewicz-Mercer 39).

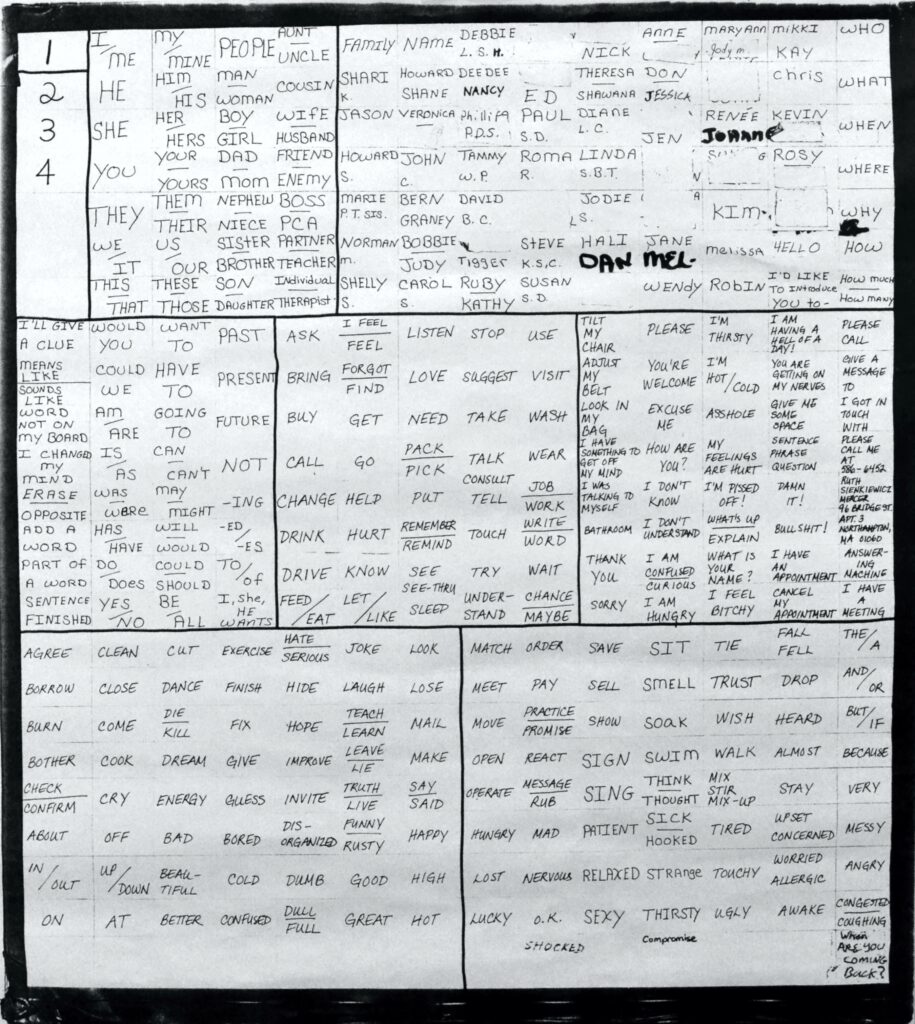

Staff ignored Ruth’s attempts to communicate with her eyes. But some other patients noticed how she spoke. Her memoir recalls long nights of giggling with her roommates, as they swapped stories by making faces. In the mid-1960s, a nurse noticed Ruth could respond with facial expressions and sounds. Decades after it was founded, Belchertown began to hire staff who specialized in education. Beginning in 1975, Ruth began using a word board. [4] As she learned to read, she added over 1,800 words, letters, and phrases to her board. She now had a tool that allowed her to communicate with others in words and sentences.

As we read about Ruth’s life, we must be clear, she did not learn how to communicate. Rather, nondisabled people learned how to communicate with her. By laughing, crying, and making different faces, Ruth could share some of her thoughts and feelings. By using the word board, she had more chances to “speak” with people around her. She became a public speaker at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and elsewhere. During her talks, she challenged what nondisabled people believed she could do. She also inspired other people with disabilities in her public speeches, “one of the themes I stressed was my lifelong dependency on other people and the fact that I was rarely respected as a woman and an individual. Through Sue’s voice [an aide who joined Ruth and spoke aloud her words], I told the audience how I had expanded my communication techniques, with hard work and lots of help, from simple facial expressions to the use of several word boards” (Sienkiewicz-Mercer 199).

Ruth also found other ways to become a self-advocate. In the late 1970s, she and other Belchertown patients moved to an apartment together. There, they lived independently with the assistance of nursing aides—aides who they insisted on helping to select. This let them have input ensuring they would get better care and respect from the staff.

Belchertown State School closed in 1992, as did many hospitals designed for people with disabilities and mental illness across the country between the 1970s and 1990s. Later in life, Ruth married one of her roommates, another ex-patient of Belchertown. Ruth passed away in 1998.

In her memoir, Ruth explained to readers how psychiatric hospitals became “custodial institutions.” This meant that hospitals became places where people might stay their entire lives and receive minimal care. Across the country, hospitals in the 1800s and 1900s held thousands of people who were unable to leave voluntarily. These people may have been incarcerated because of sensory, physical, or mental differences, or because they were misunderstood or discriminated against by family or doctors. While some individuals spent their whole lives in these facilities, others faced briefer stays. “Treatments” at these facilities could be extreme and abusive, including freezing or boiling hot baths, electroshock therapy, or medication with harmful side effects. Judi Chamberlin experienced and saw different kinds of abuse during her hospital stays. Her experiences led her to work as a disability rights advocate as part of the psychiatric survivor movement. In her memoir and advocacy guide, she wrote “many ex-patients are angry, and our anger stems from the neglect, indifference, dehumanization, and outright brutality we have seen and experienced at the hands of the mental health system. Our distrust of professionals is not irrational hostility, but is the direct result of their treatment of us in the past” (Chamberlin xiv).

Judi was born in the 1940s. After having a miscarriage and bad relationships in the 1960s, she became depressed. Judi decided to check herself into a hospital for care. Into the 1960s, she moved in and out of hospitals, sometimes against her will. There she was witness to and suffered abuse and trauma.

In 1978, the same year that Ruth moved into independent housing, Judi published On Our Own: Patient-Controlled Alternatives to the Mental Health System. This book was important to the psychiatric survivor movement. Across the country, grassroots organizations used this book to support ex-patients. The book stated that “people in emotional pain can use help,” but “we must work to change our own behavior when it distresses us, and work to help others who seek our help” (Chamberlin xiv, xvi). Based on her experiences where medical treatment led to worsening health of those needing help, Judi argued that people should support each other. This help could take different forms. It could mean educating each other about legal rights and working together to find or create alternatives to hospitalization.

Judi worked with ex-patient groups in Massachusetts, New York, and on the west coast. She stayed active from the 1970s until her death in 2010. She served on the National Council on Disability and advised the United Nations in their research on disability. Her efforts challenged mental health professionals to find new ways to support people who seek help.

The stories of these women are both exceptional and ordinary. Their writings describe the everyday experience of living with disabilities. Even though many of us can become permanently or temporarily disabled, discrimination against people with disabilities is common. And it has had traumatic and violent effects throughout American history, often for people of color and low-income individuals. Despite the success of the Americans with Disabilities Act, people continue to face barriers to healthcare, employment, transit, and safe public spaces. We must still advocate for ourselves.

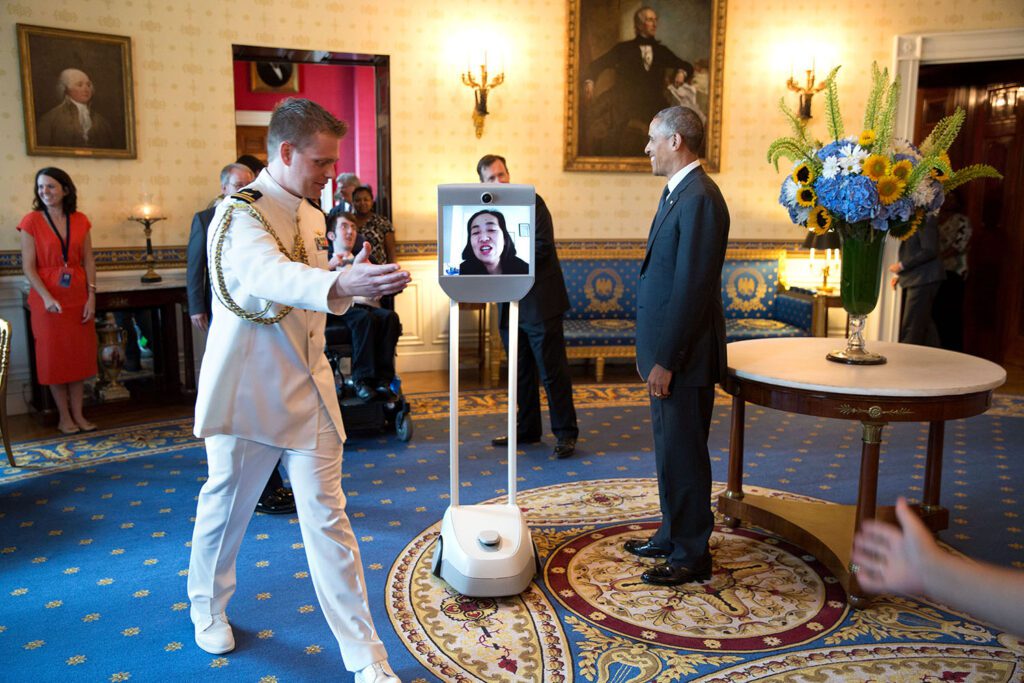

The internet is an important platform for people with disabilities to support each other. With social media, writers today like Alice Wong and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha amplify the voices of people fighting for disability justice. In the Disability Visibility podcast, Wong interviews artists, policy-makers, and self-advocates. Piepzna-Samarasinha centers on the lives of Black and brown disabled people. She focuses on the care work necessary to support one’s community and oneself. Piepzna-Samarasinha writes that this work must “come from our needs, arguments, and desires—not as window dressing with the ‘outcomes’ already decided and imposed on us” (Piepzna-Samarasinha, Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice, 85-86).

Like Judi Chamberlin and Ruth Sienkiewicz-Mercer, Alice Wong and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha challenge prejudice and discrimination, as well as the history of labeling non-white people and certain bodies and minds as “wrong.” Instead, they embrace disability as part of their identity. Their identity is central to their struggle. Compassion and peer support are necessary to combat historical injustices.

Notes

[1] According to the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, a person with a disability is “a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, a person who has a history or record of such an impairment, or a person who is perceived by others as having such an impairment.” This legal definition is contested by some members of the disability community.

[2] Ruth Sienkiewicz-Mercer co-wrote her memoir I Raise My Eyes to Say Yes (1989) with Steven B. Kaplan. Kaplan assembled her words into a story and prepared it for publication. In the book’s introduction, Kaplan explained that Sienkiewicz-Mercer edited the book, and he only submitted the draft with her approval.

[3] Belchertown State School was established in 1922 as the Belchertown State School for the Feeble-Minded. State schools and hospitals were designed as institutions for people determined to have physical and intellectual disabilities and/or mental illness.

[4] A word board is an early form of “eye gaze technology” that allows people to express ideas using their eyes.

Bibliography

Judi Chamberlin, On Our Own: Patient-Controlled Alternatives to the Mental Health System (New York, NY: Hawthorn Books, Inc., 1978).

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice (Vancouver, BC: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018).

Ruth Sienkiewicz-Mercer and Steven B. Kaplan, I Raise My Eyes to Say Yes: A Memoir (West Hartford, CT: Whole Health Books, 1989).

About the Author

Perri Meldon is a PhD candidate at Boston University and a fellow with the National Park Service. Through her NPS work, she has collaborated with parks nationwide to expand disability history initiatives. To learn more about these projects, check out her publications in the blogs of the National Council on Public History, the Disability History Association, and the American Historical Association. For more on her NPS work, visit the Telling All Americans’ Stories Disability History Series. You can reach Perri at [email protected] or on Twitter at @perri_mel.

Suggested Articles

Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray: Unstoppable Force for Justice

General George Washington and the Crossing of the Delaware

For Kids: History Of…The Postage Stamp