This article is one of a series highlighting the histories of the place we call the United States – from time immemorial to the present. Some of these histories may be familiar; some you may read about here for the first time. But we hope above all else, they make you curious about this place we live, about each other, and about what it is that makes us Americans.

Presiona aquí para ver la versión en español

A note about Henry Johnson: When researching Henry Johnson, you will find that there are several different stories about his life. For many years, Herman Johnson and his daughter Tara Johnson had claimed Henry as an ancestor. They worked tirelessly to share his story and that of the Harlem Hellfighters.[1] In 2015, when working to confirm Henry’s next of kin to receive the Medal of Honor on his behalf, researchers discovered that Henry had no living relatives. Instead, a representative of his former unit accepted the award for him.[2] But why the confusion? When Henry was born, standard birth information was not recorded by the government. He also went by Henry, even though his given name was William. And there were many others with similar names. Although Henry has no known living descendants, we are indebted to those who chose him as family and preserved and shared his story with the world.

Henry Johnson was born William Henry Johnson sometime between 1888 and 1897 in Winston Salem, North Carolina.[3] Johnson was just a teen when he moved to New York state. Like millions of other African Americans, Johnson was part of the Great Migration. They moved north out of the segregated South to find greater economic opportunities elsewhere in the United States. Johnson worked several jobs, including as a Red Cap porter at the Albany train station and as a laborer for the Albany Wood and Coal Company. Shortly after the United States entered World War I, Johnson traveled to New York City. There, on June 5, 1917, he enlisted as a Private in the U.S. Army. By enlisting, Johnson and other African Americans volunteered to defend and serve a country where they had less rights than white citizens. It was, for many, an opportunity to both serve but also to demand full citizenship and the rights that came with it.[4]

At the time, the U.S. military was segregated. Johnson was assigned to the 15th New York Infantry Regiment of the New York National Guard, an all-Black unit. The Jim Crow South did not care that African Americans had enlisted to serve their country. When Johnson’s unit was sent to train in Spartanburg, South Carolina, the mayor made it very clear that they were unwelcome. Tensions were so high that the commander of the National Guard recalled the unit to New York to prevent violence against the troops.[5]

Federalized for the war, the National Guard units were sent to Europe. Henry’s unit became the American Expeditionary Forces’ 369th Infantry Regiment. It was nicknamed the “Harlem Hellfighters” because of the large number of recruits who called Harlem home. General Pershing was the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). He did not want Black troops serving in the AEF.[6] Instead, he attached the 369th to a French army unit on the front lines. In May of 1918, in the French Argonne Forest, German troops attacked Private Johnson’s regiment. He and Private Needham Roberts were standing watch near a bridge when approximately two dozen German troops attacked. They fought back. Roberts was injured early in the skirmish, but Johnson fought on. Though he suffered 21 injuries, Johnson saved lives, including that of Pvt. Roberts. For his bravery, the French government awarded him the Croix de Guerre avec Palme (with gold palm, indicating extraordinary valor).[7] By the end the war, members of the Harlem Hellfighters had been awarded over 170 individual decorations for heroism.

On his return, Johnson was promoted to Sergeant and led the New York City parade for the 396th in February of 1919. The valor displayed by Johnson and the Harlem Hellfighters helped sway American public opinion more favorably towards African American military service. Indeed, Johnson’s image was used on posters to recruit new soldiers. President Theodore Roosevelt himself called Henry one of the “five bravest Americans” to serve in World War I.[8]

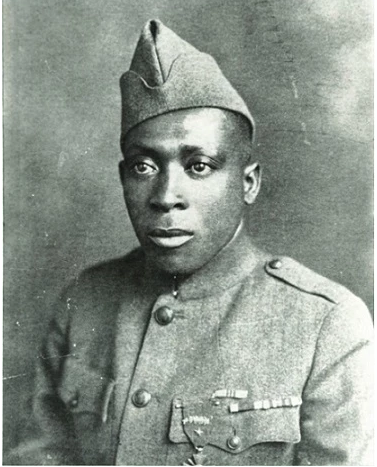

Courtesy Arlington National Cemetery.

Despite this, Johnson’s war injuries limited his ability to find work. Unable to hold down a job, Johnson turned to alcohol. He was destitute when he died, and in the mists of time, his story was largely forgotten. For decades, he was assumed to have been buried in a pauper’s field in Albany, New York. Decades later, researchers found that he was actually buried in Arlington National Cemetery, interred with full military honors. Decades after his death, Johnson was awarded the Purple Heart (1996), the Distinguished Service Cross (2002), and the Medal of Honor (2015).[9]

With the words, “The least we can do is to say, ‘We know who you are, we know what you did for us. We are forever grateful,’” President Barack Obama granted Henry Johnson the Medal of Honor. The citation reads,

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, March 3, 1863, has awarded in the name of Congress the Medal of Honor to

Private Henry Johnson

United States Army

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty:

Private Johnson distinguished himself by acts of gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty while serving as a member of Company C, 369th Infantry Regiment, 93rd Division, American Expeditionary Forces, during combat operations against the enemy on the front lines of the Western Front in France on May 15, 1918. Private Johnson and another soldier were on sentry duty at a forward outpost when they received a surprise attack from a German raiding party consisting of at least 12 soldiers. While under intense enemy fire and despite receiving significant wounds, Private Johnson mounted a brave retaliation, resulting in several enemy casualties. When his fellow soldier was badly wounded, Private Johnson prevented him from being taken prisoner by German forces. Private Johnson exposed himself to grave danger by advancing from his position to engage an enemy soldier in hand-to-hand combat. Wielding only a knife and gravely wounded himself, Private Johnson continued fighting and took his Bolo knife and stabbed it through an enemy soldier’s head. Displaying great courage, Private Johnson held back the enemy force until they retreated. Private Johnson’s extraordinary heroism and selflessness above and beyond the call of duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit and the United States Army.[10]

In honor of his service, Sgt. Henry Johnson was selected as the subject for America250’s November Salute 2021. It is on display at the National WWI Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri and online.

Notes

The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

[1] Gilbert King, “Remembering Henry Johnson, the Soldier Called ‘Black Death’.” Smithsonian Magazine, October 25, 2011.

[2] Dan Lamothe, “Army Discovers Sad Surprise in Family History of New Medal of Honor Recipient Henry Johnson.” Washington Post, June 2, 2015.

[3] When the Social Security system was instituted in the late 1930s, it required specific data to be recorded for individuals. That data included accurate birthdays. Before then, it was common for people to not be completely sure about their actual birth dates. Megan Smolenyak, “Memorial Day: Correcting the Story of World War I Medal of Honor Recipient Sgt. Henry Johnson.” Huffington Post, May 22, 2015 (updated December 6, 2017). See also Social Security Administration, “Historical Background and Development of Social Security.” Social Security Administration.

[4] WMHT, Henry Johnson: A Tale of Courage. WMHT Specials, WMHT (PBS). Air date April 10, 2017. A detail of Henry Johnson’s registration card can be viewed online.

[5] WMHT, Tale of Courage.

[6] WMHT, Tale of Courage.

[7] Army Col. Richard Goldenberg, ”Medal of Honor Monday: Henry Johnson”. Department of Defense, June 1, 2020.

[8] King, “Remembering Henry Johnson”; WHMT, Tale of Courage; Goldenberg, “Medal of Honor Monday.”

[9] King, “Remembering Henry Johnson”; WHMT, Tale of Courage; Goldenberg, “Medal of Honor Monday.”

[10] White House, “The President Awards the Medal of Honor Posthumously to World War I Veterans.” YouTube, June 2, 2015. White House Office of the Press Secretary, “Remarks by the President at Presentation of the Medal of Honor.” White House, June 2, 2015.

Bibliography

Goldenberg, Richard. ”Medal of Honor Monday: Henry Johnson”. Department of Defense, June 1, 2020.

King, Gilbert King. “Remembering Henry Johnson, the Soldier Called ‘Black Death’.” Smithsonian Magazine, October 25, 2011.

Lamothe, Dan. “Army Discovers Sad Surprise in Family History of New Medal of Honor Recipient Henry Johnson.” Washington Post, June 2, 2015.

Smolenyak, Megan. “Memorial Day: Correcting the Story of World War I Medal of Honor Recipient Sgt. Henry Johnson.” Huffington Post, May 22, 2015 (updated December 6, 2017).

Social Security Administration. “Historical Background and Development of Social Security.” Social Security Administration.

White House. “The President Awards the Medal of Honor Posthumously to World War I Veterans.” YouTube, June 2, 2015.

White House Office of the Press Secretary. “Remarks by the President at Presentation of the Medal of Honor.” White House, June 2, 2015. WMHT. Henry Johnson: A Tale of Courage. WMHT Specials, WMHT (PBS). Air date April 10, 2017.

About the Author

Megan Springate is the director of engagement for the America250 Foundation where she drives its efforts to make America’s complex, expansive histories–from local to national–accessible and meaningful to all. To do this, Springate and her team work collaboratively across America250, external communities, and partners to foster communication, teaching, learning, and engagement with America’s past and its future.