This article is one of a series highlighting the histories of the place we call the United States – from time immemorial to the present. Some of these histories may be familiar; some you may read about here for the first time. But we hope above all else, they make you curious about this place we live, about each other, and about what it is that makes us Americans.

Presiona aquí para ver la versión en español

Picture yourself on October 31st. What do you see? What do you smell? What do you hear? What are you and your friends doing? On Halloween, you might see pumpkins, witches, black cats, and ghosts decorating our neighborhoods and schools. You might dress up in a costume and go trick-or-treating. You might visit your school or community center for a party. These activities seem like long-held traditions. But Halloween celebrations as we know them today are pretty new!

If you lived in colonial America, you would not have celebrated Halloween. People in different colonies celebrated different fall holidays. Indigenous people in what is now the United States had their own fall celebrations.[1] Even after the American Revolution people did not celebrate Halloween. During these years, books called “almanacs” were published. Along with other important information, like when to plant seeds, almanacs listed important dates. Almanacs from the colonies and the early United States do not list Halloween as a holiday.[2]

Irish and Scottish immigrants introduced the traditions of Halloween to the United States. Many Irish people began moving to the United States in the mid-1840s. As many as 4.5 million Irish people moved to the United States between 1820 and 1930.[3] They brought with them their own holidays and traditions. These traditions included the celebration of Halloween. Irish and Scottish people had celebrated Halloween for hundreds of years. Their traditions were influenced by ancient celebrations like Samhain (pronounced Sow-an) and the Catholic holidays of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day. By the early 1800s, celebrating Halloween in Ireland or Scotland meant pulling pranks, playing games like bobbing for apples, and trying to guess who would be your future husband or wife.[4]

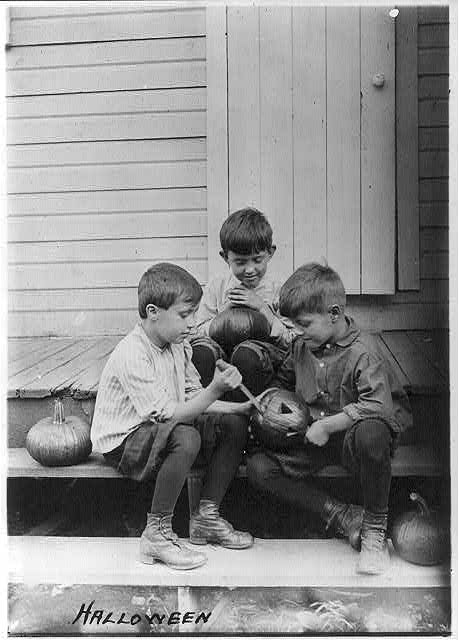

For most of the second half of the 1800s in the United States, Halloween was celebrated only by Irish and Scottish immigrants. However, other immigrant groups had similar fall celebrations. These groups found it easy to adopt these new Halloween activities.[5] New technology like railroads, telegraphs, and magazines made it easy to connect people in different parts of the country. They helped to spread new ways of celebrating October 31st.[6] More people outside the Irish and Scottish immigrant community began to celebrate Halloween. They did so in new and different ways. People played fireside games, told stories, went to parties, donated to charities, and dressed up in costumes. Other people, especially young men and boys, continued the Halloween tradition of pranking their neighbors. The holiday became less an Irish celebration, and more a night for making mischief, holding parties, and dressing up.[7]

By the 1920s, Halloween was popular across the United States. These celebrations looked similar to what we do today. People dressed up, cheered at parades, and went to parties. Popular magazines suggested ways to make your own costumes. But, if you lived in the 1920s, you still probably had not heard of trick-or-treating!

During the 1930s, people became more and more worried about the pranks being pulled on Halloween. Most pranks did not hurt anyone, but some damaged homes and cars. Many adults wanted to find a way to stop these types of pranks. They decided to start holding organized Halloween parties at schools and community centers. These parties had costume competitions, games, and dancing.[8] They were meant to get pranksters off the street. Trick-or-treating was invented around the same time with the same goal. In 1939, a woman named Doris Hudson Moss wrote a magazine article. In it she explained how she invited children to “trick or treat” at her house to keep them from pranking people in her neighborhood.[9] Children may have started trick-or-treating before 1939, but Moss was one of the first people to write about it. The combination of parties and organized trick-or-treating helped end the dangerous pranks.

In 1941, just after the invention of trick-or-treating, the United States entered World War II. During the war, sugar was rationed. When something is rationed, it means each person is only allowed to have a certain amount of it. Sugar rationing meant that there was not a lot of candy being made. Children were told that Halloween was a time to be responsible. After the war ended and sugar was more available, trick-or-treating boomed. The end of sugar rationing led to new types of candy and much more of it.[10] Most of the dangerous pranking had stopped, and it became tradition for kids to dress up in more complicated costumes to ask their neighbors “trick or treat?” In the early years of trick-or-treating, costumes were homemade. But later children could buy pre-made Halloween costumes in stores and now we can buy them online!

Today, many people across the United States celebrate Halloween in similar ways. We go to parties held at schools and community centers. We get dressed up in costumes, and go trick-or-treating with our family and friends. Irish and Scottish immigrants influenced how we celebrate today. They too were influenced by people who had celebrated Fall holidays in the centuries before them. What traditions will you use to celebrate Halloween this year?

Activity

Today, we have lots of symbols associated with Halloween. Can you think of any? The most common today are pumpkins or jack-o-lanterns, witches, ghosts, children out trick-or-treating, and black cats.

One of the most enduring Halloween traditions is telling spooky stories. Now it’s your turn! Choose two or three of the Halloween symbols discussed above and write a story that includes them. What can you come up with? For an added challenge, get together a group of family members or friends, and have them act out your story. What kinds of costumes can you design?

Notes

[1] Ellen Feldman, “Halloween.” American Heritage 52, no. 7 (2001): 64.

[2] Nicholas Rogers, Halloween: from Pagan Ritual to Party Night (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002): 67

[3] Library of Congress, “Irish-Catholic Immigration to America,” accessed July 31, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/irish/irish-catholic-immigration-to-america/.

[4] Rogers, Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night: 56-62; Anthony F. Aveni, The Book of the Year: a Brief History of Our Seasonal Holidays (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003): 125.

[5] Rogers, Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night: 88.

[6] Ellen Feldman, “Halloween.” American Heritage 52, no. 7 (2001): 65.

[7] Bruce David Forbes, America’s Favorite Holidays: Candid Histories (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015): 136.

[8] Forbes, America’s Favorite Holidays: Candid Histories: 138.

[9] David J. Skal, Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween (New York, N.Y: Bloomsbury, 2002): 52. The article Skal describes is “A Victim of the Window-Soaping Brigade?” This article was published in American Home in November 1939.

[10] David J. Skal, Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween: 55.

Bibliography

Feldman, Ellen. “Halloween.” American Heritage 52, no. 7 (2001): 63-69

Forbes, Bruce David. America’s Favorite Holidays: Candid Histories. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015.

Rogers, Nicholas. Halloween: from Pagan Ritual to Party Night. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Skal, David J. Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween. New York, N.Y: Bloomsbury, 2002.

Library of Congress, “Irish-Catholic Immigration to America,” accessed July 31, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/irish/irish-catholic-immigration-to-america/.

About the Author

Katie McCarthy received her M.A. in Public History from American University in May 2020. She loves to learn about the many surprising connections between people, events, and cultural traditions that exist in United States history. She is currently the Education Coordinator at Tudor Place Historic House and Garden in Washington DC. Her previous work includes roles with the National Air and Space Museum and the National Park Service. You can see her work on Curiosity Kits and (H)our History Lessons on the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places website.

Reading Level: Grade 8

Keywords

Colonial; Discover250; Food; For Kids; Halloween; “Histories Of…”; Holidays; International; Irish American; Nourish250; Scottish American; Share250; Tradition; World War II