Presiona aquí para ver la versión en español

This is part of a series of articles about our Founding Fathers, written for “Histories Of…” by U.S. Semiquincentennial Commissioner Val Crofts.

As we approach our nation’s 250th birthday in July of 2026, we are at a crossroads in the study of U.S. history and of creating passion and emotion about our past. The Americans who have come before us have a unique ability to reach into the present with lessons of hope and perseverance. They can also inspire us daily as we all strive to learn more about our nation and its’ history. Sir Winston Churchill once wrote that before you can inspire others with emotion, you must be swayed by it yourself.[1] To create a culture of caring about U.S. History, you need to learn about it in some way. Then, you will be inspired and be able to pass these stories down to successive generations. In this way, these histories and their lessons move to the next generation and the next. I hope that this story of a bleak, cold December day 245 years ago, will inspire you to pass it on! That was the day that General George Washington led 2,400 men across the Delaware River to save his army and our nation’s future.

General Washington’s Continental Army was a mess in the early winter of 1776. Since their victory at Boston the previous March, they had known nothing but defeat. Military defeats in New York had lost that state to the British and the British army had pursued Washington and his men across New Jersey. For safety, he had crossed the Delaware River westward and had camped in Pennsylvania. As the Continental Army camped on the banks of the Delaware, hundreds of soldiers were sick. Others had no supplies, including blankets, shoes or other items for the long winter ahead. The army had lost about 90 percent of its strength since the battles in New York. Support from patriotic citizens had gone away and many of Washington’s soldiers, who felt that the cause of independence was lost, were looking to go back to their homes on January 1, 1777, after their time in the army was completed. General Washington was worried as he wrote on December 17, 1776 to his brother, Samuel, “I think the game is pretty near up.” The creation of the nation that would come to be known as the United States was in jeopardy.

General Washington still believed that the war could be won if he could achieve even a small victory to stop the recent string of defeats. This would boost morale in the army and among the citizens of the United States and could turn the war around. He would also have an opportunity to capture war materials, as well as food and clothing to assist his army. Washington’s army would need to go on the offensive and he had an idea. His opportunity was in the village of Trenton, which was across the Delaware River in New Jersey.

Trenton was a very important military post, manned by 1,400 Hessians. Hessians were German troops hired by the British to fight for them during the American Revolution. The Hessians’ weapons and supplies would be a tremendous help to Washington’s army — if they were able to capture them. Their commanding officer, Colonel Roll, had his troops on a state of high alert in case of an attack by the Continental Army.

Washington’s battle plan was to divide his army into 3 parts and each would cross the Delaware River as part of the attack on Trenton. General Washington would serve as field commander and lead part of the attack personally. This was the first time in the war that he had done this, but he believed that this operation was too valuable to have someone else lead it. The attack was to take place under the cover of darkness and surprise the Hessians before they could wake up and fight back. If he succeeded, the war would go on and his men would be better supplied, with morale improving. If he lost, the war would most likely end and he would be executed for treason. It was “Victory or Death” for the army and that slogan became the password for the attack. The crossing was to take place on Christmas night.

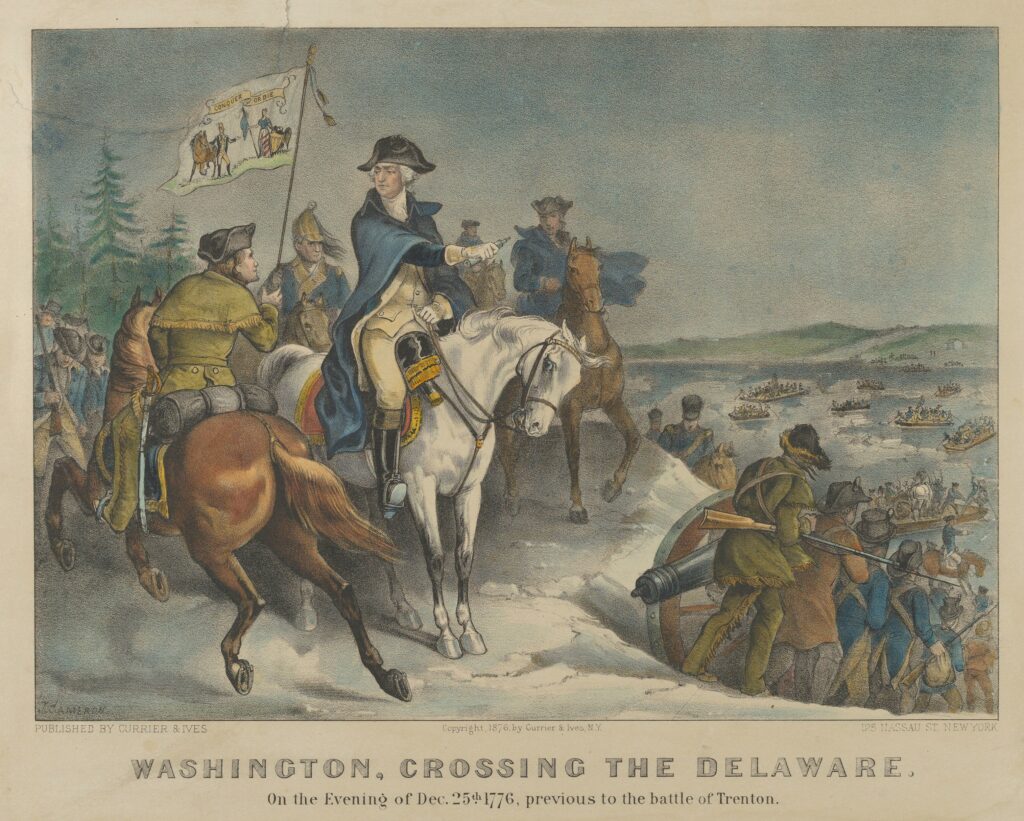

Although George Washington led the attack on Trenton, several others also contributed to its success. General Henry Knox, Washington’s chief artillery officer, was in command of the crossing. He was responsible for getting the approximately 2,400 men, 50 horses, and 18 cannons safely across the river. Knox’s booming loud voice was heard shouting instructions throughout the loading of the boats. General John Glover and his Marblehead militia from Massachusetts served as crews of the 40 to 60 foot long Durham boats that transported Washington and his army across the Delaware River that night. Future president James Monroe crossed with Washington, and is depicted holding the flag in Emanuel Leutze’s famous painting, “Washington Crossing the Delaware.” Alexander Hamilton, one of Washington’s aides, was sick during the day but got himself out of bed to make the crossing with the rest of his fellow soldiers. Also among these famous men were countless others, from teenagers to old men, who made the crossing and entered into history.

The crossing was almost called off due to bad weather. As the men gathered at the shoreline around 4:00pm on Christmas to begin the crossing, a cold rain began to fall. It continued to rain as they loaded the boats. Over the next 11 hours, General Glover’s men rowed back and forth across the Delaware River, successfully carrying 2,400 soldiers and their equipment to the New Jersey shoreline. As the night went on the weather worsened. The cold rain turned into freezing rain, sleet, and snow. The men were covered in ice and snow and the river became treacherous as solid ice formed and had to be broken up for the boats to pass. Miraculously, there were no fatalities during the crossing itself. But not everything was going well. Of the 3 parts of the Continental Army who were supposed to attack that night, only those with Washington made it to their destination. The other 2 had turned back due to the extreme weather.

Around 3am on December 26 — 3 hours later than hoped — the last of Washington’s men made it across the river. Cold and wet, they faced a nine mile march to Trenton. And although they would not have the darkness they planned on to cover their movements as they approached the town, they did have the cover of a blizzard that made visibility very difficult. The trek followed a path that was rocky and covered with snow and ice. Many of the troops later said the march was the worst part of the night, as the weather kept getting worse. During the march, soldiers realized that their gunpowder had gotten wet and would not fire. Washington advised them to use their bayonets instead, if necessary. As the march got closer to Trenton, the feet of soldiers with no shoes left bloody footprints in the snow.

As Washington’s troops approached Trenton, Nathaneal Greene led the first attack. The 1,400 Hessian soldiers serving under Colonel Rall were in their barracks, resting and taking shelter during the horrible weather. Many histories tell us that the Hessian troops in Trenton that morning were drunk. They were not. They were actually anticipating an attack but did not know when. Earlier that day, Rall had received intelligence that the Continental Army was advancing on Trenton. Believing that no one would attack during the winter storm, he and his men took the opportunity to get some rest.

When they were about 200 yards away, the Hessians spotted Washington’s forces. Despite the weather, here the Continental Army was, marching toward his troops. After a 45 minute battle, the Continental Army had scored a major victory with a very minimal cost. Washington’s soldiers captured military supplies and several barrels of rum. The casualties for Washington’s army were relatively light. They included 4 wounded (including future president James Monroe) and two who died of exposure during the march to Trenton. Before leaving Trenton, several of Washington’s soldiers helped themselves to the captured rum. They then had to march back to Pennsylvania while drunk.

The march and river crossing back to Pennsylvania was in weather even worse than during their approach to Trenton. After marching the 9 miles back to the river, the men again boarded the boats. They were cold and exhausted. Some of them had been awake for over 50 hours. Three of Washington’s men fell into the Delaware River and drowned on the return trip.

Washington had achieved his greatest military victory of the war. He had brought the army out of the despair that it had been feeling. He had supplied the men with clothes, food, and military supplies. He had turned public opinion back in favor of the war, and he had convinced many of his men that the war could be won. Even though they could have returned home at the beginning of the year, many chose to re-enlist and stay in the army. He had restored hope in the army and in his men. He had inspired the soldiers with his leadership and bravery against strong odds against him. He and his army had persevered through a long stretch of defeats and had come out, victorious, in Trenton.

As we begin to emerge from the past almost 2 years of the COVID crisis, we can use these lessons that General Washington exemplified and apply them to our lives today. Just as Washington and his army persevered despite overwhelming odds, we continue to persevere through COVID. And here we are. Ready to face the future and the next challenges that our nation will face. We can also take inspiration from today’s heroes. These people include front line workers and community heroes that have helped guide us through the past 2 years. They are an inspiration to us all. As Washington led his soldiers into the crossing of the Delaware 245 years ago and rejuvenated a nation’s spirit to carry on, these workers and heroes have done the same for us today.

Notes

[1] Winston S. Churchill, “The Scaffolding of Rhetoric.” November 1897. This essay, originally unpublished, has been made available online by the International Churchill Society.

Bibliography and Recommended Reading

Chernow, Ron. Washington: A Life. London: Allen Lane, 2010.

Churchill, Winston S. “The Scaffolding of Rhetoric,” November 1897. International Churchill Society.

Ferling, John. Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Fischer, David Hackett. Washington’s Crossing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Gingrich, Newt and William R. Forstchen. To Try Men’s Souls: A Novel of George Washington and the Fight for American Freedom. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2009.

McCullough, David. 1776. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005.

O’Donnell, Patrick K. The Indispensables: The Diverse Soldier-Mariners Who Shaped the County, Formed the Navy, and Rowed Washington Across the Delaware. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2021.

About the Author

Val Crofts is a member of the America250 Semiquincentennial Commission, which is currently planning the national celebration of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 2026. He is a lifelong student of history and a student and admirer of General George Washington.

Keywords

Colonial History; Discover250; “Histories Of…”; Holidays; International; Massachusetts; Military; New Jersey; Pennsylvania; Revolutionary War; Salute250; United States Presidents

America’s Field Trip Awardees!

Thousands of students from across the country submitted inspiring entries, responding to the prompt “What does America mean to you?” for the first-ever America’s Field Trip contest. A panel of current and former educators selected 150 students as awardees, hailing from 44 states and territories.