Grass Route

Words by Steve Wulf with photographs by Jean Fruth

What do Route 66 and baseball have in common?

Let’s start where The Mother Road does, at the corner of Adams Street and South Michigan Avenue in downtown Chicago. It’s equidistant from Wrigley Field on the North Side and Comiskey Park on the South Side. Because his grandfather ran the Cubs and his father owned the White Sox, longtime baseball executive Mike Veeck has a deep appreciation for the storied highway: “It’s the Yellow Brick Road that leads you to Oz and the Emerald City.”

Indeed, as a youngster, Veeck lived very close to the iconic Begin sign. From there, on the western shore of Lake Michigan, Route 66 heads south and passes through the heart of America, both literally and figuratively—just like The National Pastime. As it makes its way to the Pacific, the road threads countless towns and endless vistas while a million dreams are played out on the sparkling baseball diamonds on either side.

They can both seem endlessly long—the number of miles of Route 66 (2,448) is remarkably similar to the number of major league games played in 2021 (2,428). Yet they always leave us wanting for more. Consider that America’s Highway and America’s Game have inspired such Great American Novels as The Grapes of Wrath (1939) and The Natural (1952), popular movies like Cars (2006) and Field of Dreams (1989), and songs we can never get out of heads, i.e., “Route 66” (1946) and “Take Me Out To The Ballgame” (1908).

But what truly makes these two timeless wellsprings a match for one another is that both beckon us to leave home… and then welcome us back.

That deep connection between the highway and the game is explored in the book, Grassroots Baseball: Route 66. Edited by former Baseball Hall of Fame President Jeff Idelson, this celebration puts you in mind of a wonderful road trip. Gaze out the window, and you’ll see the beautiful, evocative images of photographer Jean Fruth. Over there, three members of the Binger (Oklahoma) Bobcats riding in the back of a 1968 Chevy pickup on their way to a game. Over here, the broad side of a barn in Nilwood, Illinois with the Betsy Ross version of the Stars and Stripes as a target. Look—a sliding player creating his own Dust Bowl.

And as you sit back, listen to the words of guides who have been there before—Jim Thome, Ryan Howard, Johnny Bench and George Brett, just to name a few. These are just some of the players who contributed to the book. Bench, who hails from Binger, is particularly proud of all the baseball greats who have come from The Sooner State. “I’d bet you that if your state and my state had a pickup game,” he writes, “we would beat you.” Having Mickey Mantle from Commerce, Oklahoma, certainly helps.

Route 66 goes by another name: “The Will Rogers Highway.” The American folk hero was also an Oklahoma native, born in Oologah, a tiny town on a Cherokee reservation, in 1879. He made a name for himself as a cowboy on the vaudeville stage, but his true calling was as a social commentator on the radio. He once told America, “Baseball is our national game. Every boy and girl in the United States should play it. It should be made compulsory in the schools.”

As it happens, Rogers was an avid fan of the St. Louis Cardinals, and he rejoiced when the Cards beat the vaunted New York Yankees in the seventh game of the 1926 World Series. That victory was especially significant because by winning the Series, the Cardinals became the first team west of the Mississippi to win a championship.

Lo and behold, one month after baseball expanded its western horizon, Route 66 was officially established. The next year, to garner publicity, a foot race from Los Angeles to New York City called “The Bunion Derby” was run. Rogers greeted runners at several stops along the way. By the time the 1932 Summer Olympics were held in Los Angeles, Route 66 had become “The Main Street of America.”

The signposts along the way weren’t just big stadiums. They were also the sandlots, playgrounds, and Little League diamonds that produced some of the greatest players in baseball history. Players like Thome, the Hall of Famer who grew up in Peoria, Illinois — 58 miles west of the Route 66 Hall of Fame in Pontiac, Illinois. In fact, his father was a foreman for Caterpillar, the equipment company that helped build The Mother Road. “Little did I know,” writes Thome, who was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2018, “that hitting all those rocks in our gravel driveway on South Crest Drive would lead me to a 22-year major league career.”

Springfield, Illinois, which is right on 66, is best known as the town that sparked the political aspirations of Abraham Lincoln. But it’s also the backdrop for Thome’s entry into the pros. Between games of a doubleheader between his Illinois Central College team and Lincoln Land Community College, a scout from the Cleveland Indians (now the Cleveland Guardians) sidled up and asked him if he would sign if they drafted him. According to Thome, “It was what I had been dreaming about all along.” They did, in the lucky 13th round.

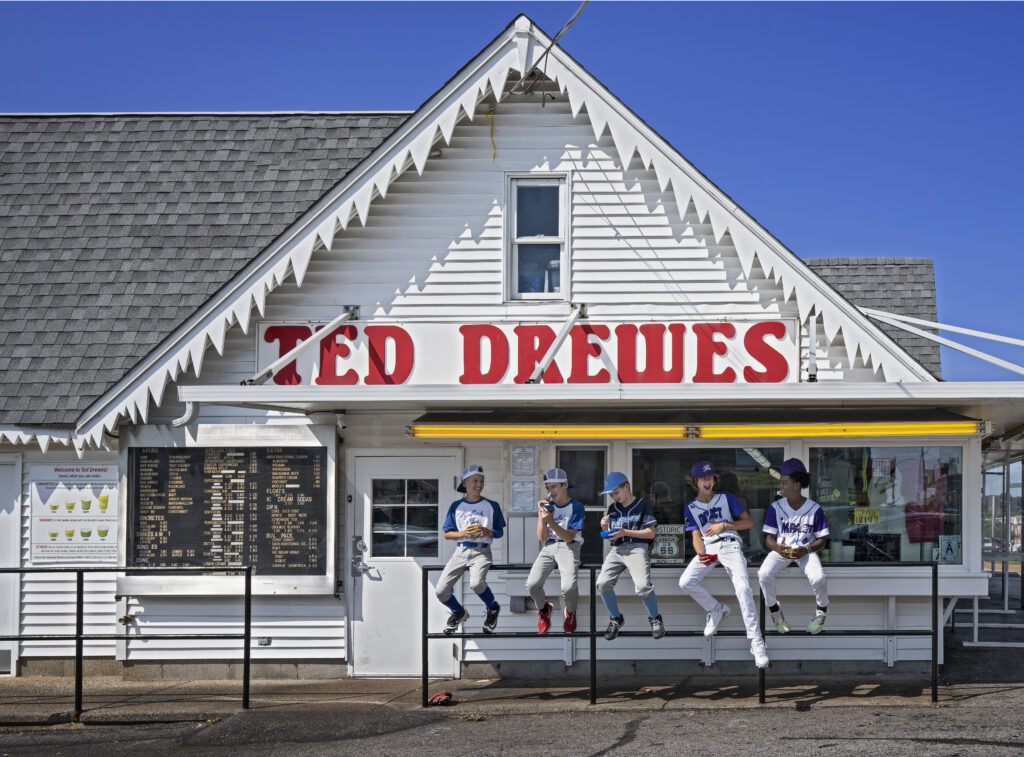

Travelers can’t miss the border between Illinois and Missouri—it’s the Mississippi River. And waiting on the other side is the Gateway Arch, the magnificent stainless-steel monument designed by Eero Saarinen and completed in October of 1965. Ryan Howard, the 2006 National League MVP for the Phillies, grew up on the outskirts of St. Louis in the shadow of the Arch. He recalls going there on field trips and taking the tram to the top to look down upon Busch Stadium and out to his future. After playing football, basketball, baseball, and the trombone at Lafayette High School, he chose to go through the Arch to attend Southwest Missouri State in Springfield, Missouri. He loved the drive along Route 66, from Ted Drewes Frozen Custard in St. Louis to one of the original Steak & Shakes in Springfield. “But the trip wouldn’t be all about food. There’s Purina Farms and Meramec Caverns and the Jesse James Wax Museum and Devils Elbow and the World’s Largest Rocking Chair.”

Route 66 makes just a brief, 13-mile appearance in Kansas, crossing the Missouri border and hanging a hard left into Oklahoma. Even so, there’s a baseball connection in that corner of the state, thanks in large part to the LaRoche family from Fort Scott. Together, Dave LaRoche and his sons Adam and Andy logged 32 seasons in the majors. “We had the best of both worlds,” writes Adam. “Small town America and big-league baseball.” Adam also points out that down the road in Baxter Springs, Jesse James once robbed a bank and Bonnie and Clyde helped themselves to some cash while passing through. In considering his good fortune, Adam writes, “Sometimes I feel like I robbed a bank.”

In his Oklahoma entry, Johnny Bench suggests that the Route 66 sign at the state’s northeast border should also carry the message: Baseball Ahead. Hall of Famers Paul and Lloyd Waner, Willie Stargell, Iron Joe McGinnity, Bullet Joe Rogan, Dizzy Dean, Warren Spahn, Bench, and Mantle are counted as Sooners. In fact, one of the first towns you come to when you cross over from Kansas is Commerce, where the water tower wears Yankee pinstripes and the No. 7. In Commerce, Route 66 also goes by the name of Mickey Mantle Boulevard, and Mantle’s boyhood home at 319 South Quincy Street is preserved as a shrine to the great Yankee centerfielder.

Bench grew up in Binger, 250 miles west of Commerce, worshipping Mantle. As it turned out, the first of Bench’s 14 All-Star Games was the last of Mantle’s 20. Binger, an agricultural town, was a lot smaller than Commerce. How small? Here’s how the Reds catcher describes the start of the parade the town gave for him after he won the National League MVP award in 1970: “When we got to town, NOBODY WAS THERE! Everybody was in the parade.”

The next state for Route 66 is Texas, more specifically the Texas panhandle. It’s a land of oil fields, minor league baseball past (Jim Bouton pitched here) and present (the Sod Poodles), and the Cadillac Ranch — a series of artistically painted Cadillacs buried hood-first into the ground.

The days of those Caddys are over, but the highway they once ruled comes to vivid life across the New Mexico border in Tucumcari, where the Blue Swallow Motel inspired the Cozy Cone Motel of the Disney movie Cars. Alex Bregman, the All-Star third baseman for the Houston Astros, knows the town well because he often drove from his hometown of Albuquerque to his alma mater, Louisiana State. “I can tell you, the neon lights of Tucumcari will keep you awake,” he writes in the book.

When Route 66 reaches Albuquerque, it becomes Central Avenue and leads you to Old Town. As Bregman recalls, “My school always had a field trip to Old Town. The Indian Pueblo Cultural Center is very interesting, but the biggest attraction is the Rattlesnake Museum—even though I’m scared of snakes, I have to admit it’s pretty awesome.” His favorite memory, though, is going to the morning show at the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta the first week in October. “There I am, holding a cup of hot chocolate while eating a breakfast burrito and watching these magnificent balloons take off.”

Billy Hatcher broke into the majors where Route 66 begins, as a Cubs outfielder in 1984. He retired after helping seven teams in 12 seasons and breaking Babe Ruth’s World Series record for batting average in a series—he hit .750 for the Reds when they swept the A’s in 1990. But he’s very much a child of Williams, which is on The Mother Road in the center of Arizona, at the start of The Grand Canyon Railway that takes visitors to that natural wonder.

The 5’9” Hatcher was All-State in football, basketball, baseball, and track, so there were plenty of trophies for him to collect. But the best one has to do with Rod’s Steak House, the legendary Williams restaurant that opened in 1946 during the heyday of Route 66. In Hatcher’s retelling, “They still kid me about the night my friends celebrated a big game I had by rolling that big porcelain bull in front of Rod’s all the way down Route 66 to the Coffee Pot Restaurant, where I like to have breakfast. They wanted to let me know that I was the Big Bull.”

U.S. 66 crosses its last state border in the middle of the Mojave Desert, where it brings us to Needles, California. The last stretch of America’s Highway is a study in contrasts as it leaves the Devils Playground in the Mojave National Preserve and heads toward the City of Angels. “I grew up in El Segundo, which is two beaches and one gigantic airport down from the end of Route 66,” writes Hall of Fame third baseman George Brett. “But you couldn’t help but see the starlight to the north… I’m old enough to remember watching Route 66, starring Martin Milner and his Corvette.”

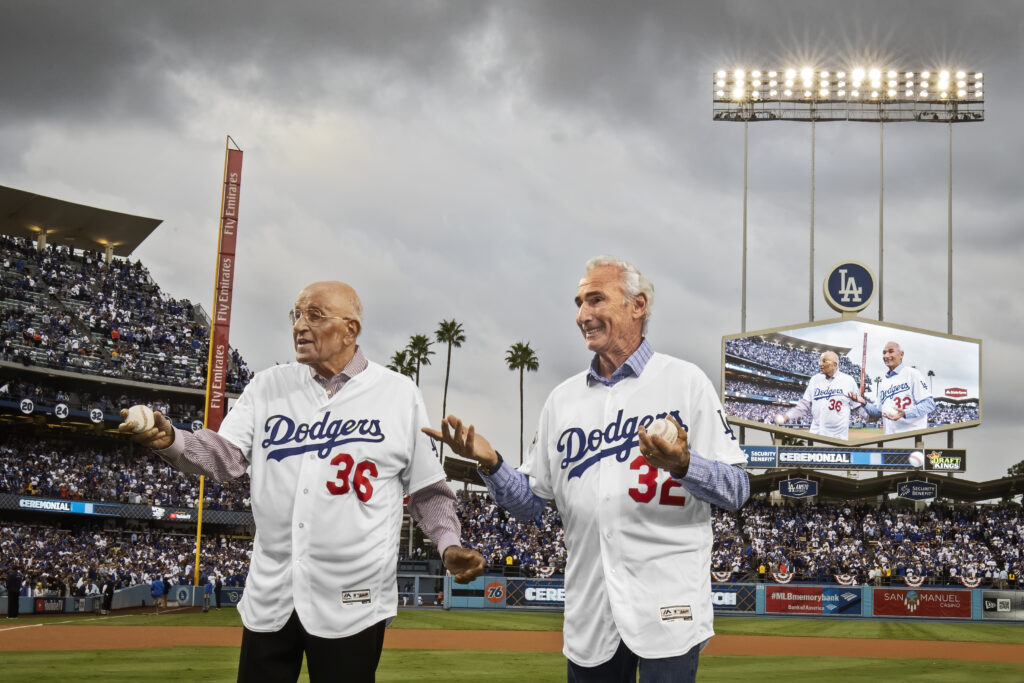

For Brett and his three older brothers, there were baseball games to attend at Dodger Stadium, where they pestered Hall of Famers like Sandy Koufax for autographs, and just as importantly, games to play when their chores were done. When Ken Brett signed with the Red Sox and at 19 became the youngest pitcher in World Series history in 1967, 14-year-old George suddenly found himself on the Red Sox team bus with Carl Yastrzemski, whose swing he had borrowed.

It really did feel like The Emerald City to Brett. He points out that the last 25 miles of Route 66 take you past the Rose Bowl, Dodger Stadium, UCLA, Beverly Hills, and Hollywood before reaching the Pacific at the Santa Monica Pier. Leave it to a man who knows them both so well to come up with the perfect metaphor.

“If America were a baseball game,” writes Brett, “then Route 66 would be its walk off homer.”

About the Author

By Steve Wulf, who has written about baseball in six different decades, mostly for Sports Illustrated, Time and ESPN, and serves as a Grassroots Baseball® advisor.

Photographs by Jean Fruth from her book Grassroots Baseball: Route 66, available at www.grassrootsbaseball.org.

Bibliography

Quotes: From the book Grassroots Baseball: Route 66

Statistics: From Baseball Reference

Content: SABR Bio Project

Content: The Best Hits On Route 66, by Amy Bizzari, Globe Pequot, 2019

Content: Route 66 Road Trip, by Jessica Dunham, Avalon Travel 2021

Keywords

Sports; Baseball; Route 66; Illinois; Oklahoma; Missouri; Texas; New Mexico, California

Suggested Articles

William Howard Taft’s Children

Self-Advocacy and U.S. Disability History

Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray: Unstoppable Force for Justice