This article is one of a series highlighting the histories of the place we call the United States – from time immemorial to the present. Some of these histories may be familiar; some you may read about here for the first time. But we hope above all else, they make you curious about this place we live, about each other, and about what it is that makes us Americans.

Presiona aquí para ver la versión en español

The holidays and birthdays are times that many people still send messages to each other the old-fashioned way: through the post office.

A big idea that led to a very small invention changed the way people around the world communicate.

Imagine your surprise if someone knocked on your door, gave you a letter, and then asked you to pay for it. If it was a letter from a friend you would be happy to pay. But if it was junk mail or bad news, you might refuse to accept it.

Before the invention of postage stamps, this is how the mail worked. The cost of mail was usually paid by the person receiving it, not the person sending it. And it was often expensive! The cost was based on how far the letter traveled and how many sheets of paper it had.[1] This system was a problem when the person receiving the letter could not afford to pay or did not want to. Some people used tricks and sent secret messages on the outside of the letter. This way, the person receiving it got the news, but didn’t have to pay. When people refused their mail, the post office returned it to the sender. This cost the post office a lot of money.

Sending mail became much easier (and cheaper) when Sir Rowland Hill invented the postage stamp in 1837. He was a school teacher in Great Britain. But he was also interested in making the world better. After doing research, he wrote a proposal to the British government. He suggested that the person sending the mail pay for the postage. And he proposed that the cost of sending a letter be the same, no matter how far it had to travel or how many pages it had. Sir Rowland Hill argued that a low, standard cost to send a letter would mean more people would use the mail. This would, he said, increase profits. The job of the stamp was to prove that the postage had been paid.[2]

Members of the British government thought his idea was silly. They called it preposterous and a wild scheme. But merchants and other members of the public thought it was a good idea. They contacted their government representatives and asked them to give it a try. In 1839, Sir Rowland Hill got a contract to try his system. It was a success!

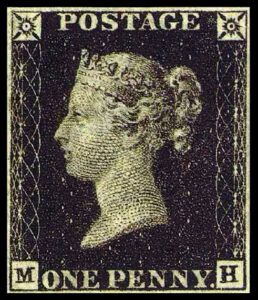

The first stamp in the world had an image of Great Britain’s Queen Victoria. First sold in 1840, people nicknamed it the “Penny Black.” The name came from the black ink used to print the stamp, and the fact that it cost a penny to buy. Governments around the world paid attention to Great Britain’s experiment.

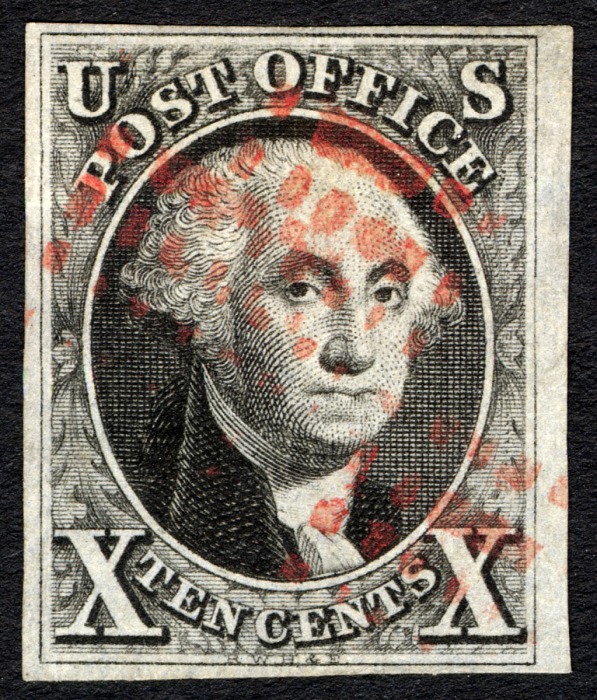

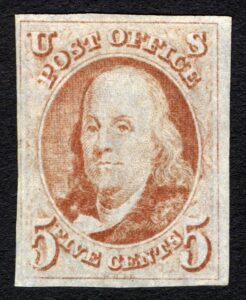

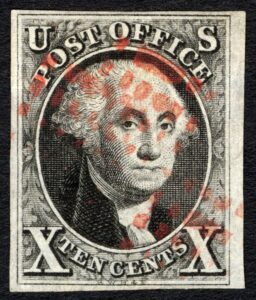

The United States issued its first two postage stamps in 1847. One was a five-cent stamp that honored Benjamin Franklin. In 1775, even before the Declaration of Independence, Franklin was put in charge of what would become the U.S. Postal Service. The other stamp issued in 1847 was a ten-cent stamp of George Washington, the first U.S. president.[3]

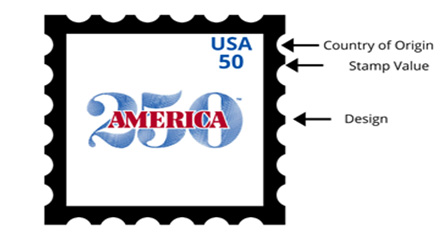

What Makes a Postage Stamp?

A stamp usually includes the country it is from, its value, and a design or image. On the back is a sticky substance (an adhesive) to keep the stamp stuck on the envelope. Stamps are printed in large sheets, with many stamps on each one. Early on, people cut the stamps off the sheets with scissors. In 1857, perforations appeared. These are small holes around the edges of each stamp in a sheet. These allowed people to tear stamps free of the big sheets instead of needing scissors. Perforations leave the small scalloped edges around individual stamps that we are familiar with.

There are many different types of stamps. Different values are used for mailing different weights and types of mail. Designs on stamps range from patriotic (like flags and presidents) to commemorative. Commemorative stamps mark an important anniversary, person, or event. Other designs are also found.[4]

A stamp is not only for mailing letters. They are also like small time capsules. The images show what people at the time thought was important enough to be on their country’s stamp. The differences in values give information on the history of the post office. A collection of stamps from different times and places can give you a sneak peek into history.

Complete the below activity to design your own stamp, tell a story, and show pride in where you come from!

Activity: Design a Postage Stamp

Think about where you live and what is important to you. Think about how you can represent these things on a stamp. Maybe it is your state’s flower or bird. Maybe it is your favorite food or animal. Maybe it is a place that you love. Or a family member or historical figure that is special to you. Use the blank stamp outline to design your stamp. Don’t forget to include the basics: your country of origin, the stamp value, and image.

If you want to share your design with us, ask an adult in your life to post it to social media and tag us (Facebook: #America250; Twitter: @America250; Instagram: @250America).

Notes

[1] The Postal Museum, “Rowland Hill’s Postal Reforms.” The Postal Museum, London.

[2] John Ross (1998) “Stamps. What an Idea!” Smithsonian Magazine, January 1998; Congressional Research Service (2013) Common Questions About Postage and Stamps (pdf). April 19, 2013. Congressional Research Service, Washington, DC.

[3] Ross (1998) “Stamps. What an Idea!”

[4] United States Postal Service (2020) “About: Stamps and Postcards.” United States Postal Service.

Bibliography

Congressional Research Service (2013) Common Questions About Postage and Stamps (pdf). April 19, 2013. Congressional Research Service, Washington, DC.

The Postal Museum. “Rowland Hill’s Postal Reforms.” The Postal Museum, London, England.

Ross, John (1998) “Stamps. What an Idea!” Smithsonian Magazine, January 1998.

United States Postal Service (2020) “About: Stamps and Postcards.” United States Postal Service.

About the Author

Maricela Dominguez is the engagement coordinator for the America250 Foundation. Dominguez supports public programs that enhance the teaching and learning of America’s complex and expansive histories. She and her team collaborate across America250, external communities, and partners to make the commemoration the largest and most inclusive commemoration in our nation’s history.

Dominguez is a proud graduate of Florida International University with a bachelor’s degree in Public Administration and a minor in Social Welfare. She is committed to moving communities forward through education, amplifying diverse narratives, and sustainable development.